September 3, 2020 by Anchor contributor Janice Brown McPhillips

Here is something we can all agree on - despite some rain in the last ten days, this summer of 2020 has been a hot and very dry summer. Even before we in Hingham owned our water utility, I personally have been worried about all the water homeowners pour onto their lawns every year. The water system we just purchased makes clean and safe drinking water for us. But we don’t own the water in the streams, ponds, and underground wells and drought affects the quantity of water in those resources available to all of us. The state Department of Environmental Protection sets the limit on the number of gallons that the town can draw from its resources every year to provide water to its customer base, which includes residents and businesses. That limit is currently 65 gallons per person per day. The only way we can be certain that there is enough water for us to drink, cook, and clean, leaving enough for wildlife and fighting fires is to conserve what we have.

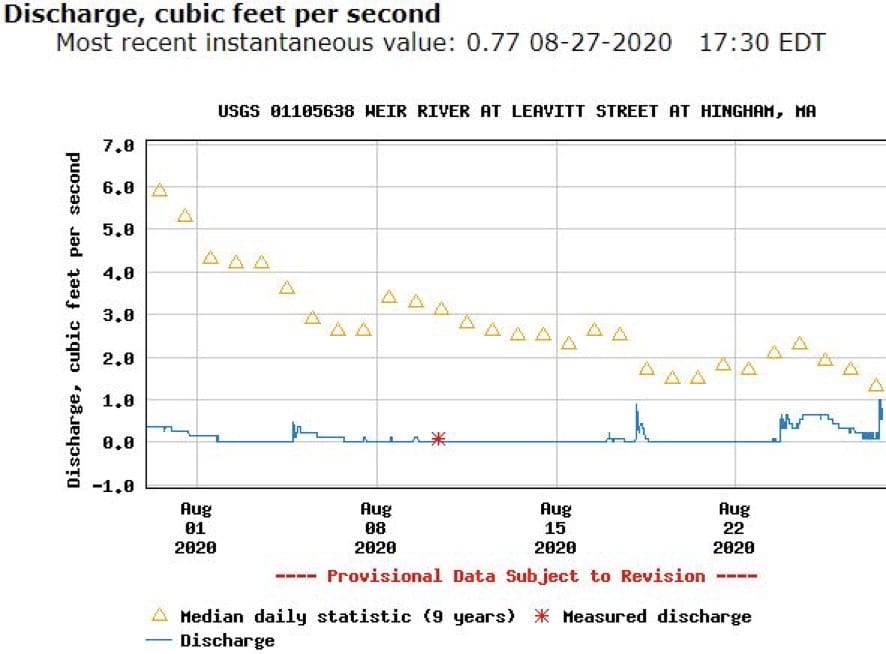

On or near August 1, 2020, the USGS (United States Geological Survey) gauge at Leavitt St on the main stem of the Weir River recorded zero flow and has stayed that way, or pretty close to it since then. Tough if you are a fish or other wildlife depending on this resource.

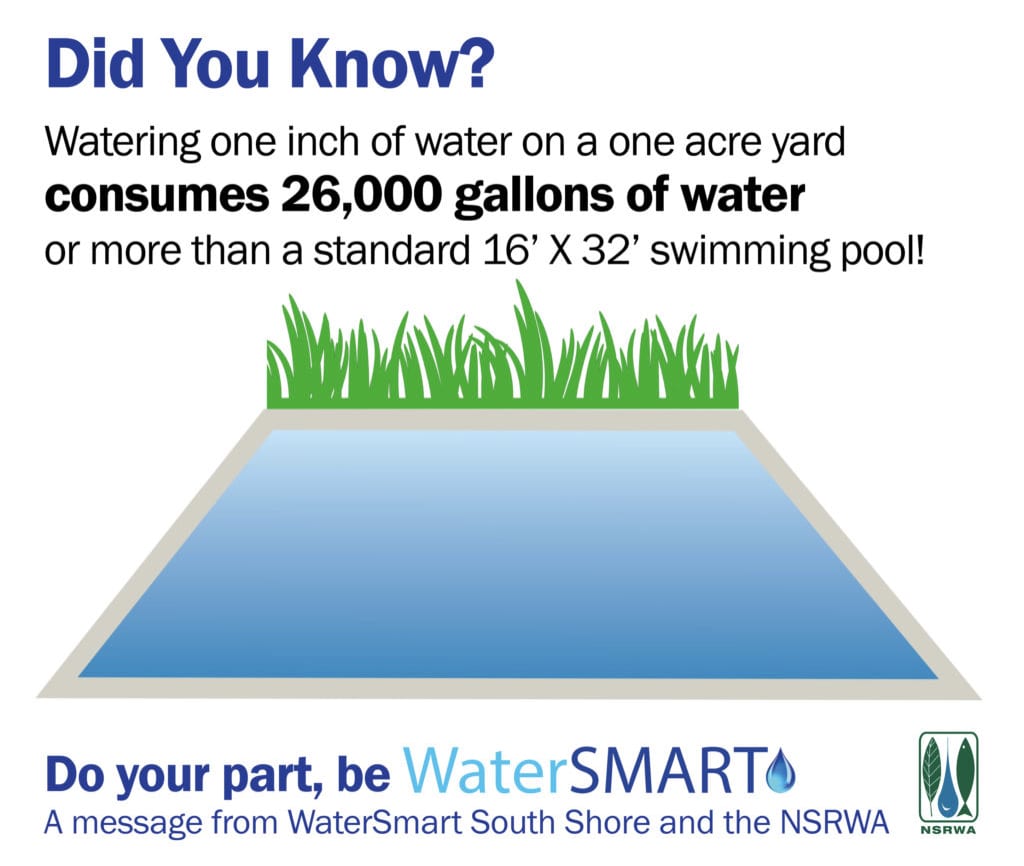

The National Wildlife Federation estimates that a whopping 50-70% of residential water is used to irrigate lawns. A study done by NASA in 2005 found that over 40 million acres of grass was planted in the continental US, making it the largest irrigated crop we grow. That’s more than all the acres of corn, wheat, and fruit trees growing in this country combined. To get a sense of the scale of our lawn watering habit, irrigating the recommended one inch of water over an acre of lawn uses 26,000 gallons of water! Compare that to the 65 gallons per person per day recommended by Mass DEP for Massachusetts residents.

Our passion for lawns dates back to the 16th-century English countryside where lawns were cultivated in the cool, damp climate of the area. In the early history of this country, grass was planted to feed animals. Most of us who live in the suburbs are certainly not feeding livestock on our lawns. I like the look and the feel of soft green grass as much as the next person. Walking barefoot on it feels good, and tossing a ball to a child or a dog is fun - but green grass comes with a huge cost, both to our pocketbooks and the environment. According to Samantha Woods, Executive Director of the North and South Rivers Watershed Association and also board member of the Weir River Watershed Association, “the right time to water a lawn is never.” Ouch! We all need to reconsider the importance of that green lawn, especially given that we seem to be in a pattern of very hot and very dry summers here in New England. And to those of you who water your lawn with well water, please consider that your well draws water from the same underground aquifer that the town draws from. You are legally permitted to use that water to irrigate your lawn, but is that the right thing to do during a drought?

If you have let your lawn go dormant this summer like we have, congratulations and thank you for doing your part to conserve water. If you are thinking about it and wonder what your non-irrigated yard could look like, there are options to consider. One is to completely eliminate the lawn - a tough sell for some - but there are examples of local homeowners who have converted their grass into meadows for pollinators, rain gardens, or raised bed vegetable gardens. For other examples and inspiration, visit www.foodnotlawns.com - it’s a website, it’s a book, it’s a movement. I doubt that Hingham will ever become like Todmorden, a former mill town located about 17 miles northeast of Manchester in the UK where food for the community is growing in yards, parks and vacant lots all over the town. So if that is too drastic of a step for you, consider planting a yard of native strawberries or other low growing native perennial that not only tolerate drought but provide food for native pollinators like bees. Or, if you just can’t kick the grass habit, consider the way you manage your grass by overseeding with drought-tolerant varieties like fescues. You can find more healthy landscaping techniques visit watersmartsouthshore.org or to go completely native, visit https://www.masswildones.org/

Most importantly, know that grass is meant to go dormant in hot weather and you can completely stop watering your grass and it will recover when the weather cools in the fall. So lets all do a little something for the environment during this significant drought. Turn off the automatic sprinklers if you have them - the grass will be green again in September. Water your gardens using soaker hoses or handheld hoses so water stays where you want to deliver it and doesn’t go running down the driveway. And rethink that lawn and consider more environmentally friendly ways to surround your home with plants that don’t require as much care and water as grass.

Janice Brown McPhillips is a Hingham resident who works at Holly Hill Farm in Cohasset as a Farm and School Garden Educator, a member of the Cleaner Greener Hingham Committee and Garden Coordinator of the Weir River Farm Community Garden.

The author would like to acknowledge contributions from Samantha Woods who is the Executive Director of the North and South Rivers Watershed Association, Board Member of the Weir River Estuary Committee, and member of the Massachusetts Water Resources Commission.

Thank you. The article is enlightening. Weather patterns are indeed changing, and there are creative ways we can adjust.